Which Shall It Be?

Liberty or Equality, Americanism or Marxism

By R. Carter Pittman

Address delivered before the Annual Convention of the

Alabama Bar Association, Montgomery, Alabama, July 16, 1954

(Published in the Congressional Record of Saturday, July 31st, p. A5624)

SEVERAL years ago J. Edgar Hoover asked Herbert Philbrick, a quiet, humble church worker of Massachusetts, to go underground and become a “Communist” for his country. For 9 years Philbrick was an FBI counterspy deep in the Communist underground. Finally he emerged and is now on the staff of the New York Herald Tribune. Speaking in Arkansas recently he said;

One of the great problems which we have in dealing with communism is the fact that there seems to be in the minds of the American people certain blind spots.

He then described how the Communists have reduced deception to a science — the science of filling in blind spots with falsehood and misleading people by “scientific” thought control. The Communists call that system “cybernetics.” It is the control and falsification of information. It is hyprocrisy in red robes.

Empty minds, like empty stomachs, grab at any bait. Man learned that as a jungle dweller. Russians claim to have just discovered it. Cybernetics therefore consists of the elevation of the lowest level of human depravity to the dignity of sociological “science.” Its name sounds learned. As usual, many who wish to appear learned become fellow-travelers, and Communists use them as a front. Fellow-travelers usually call themselves and call each other “doctors” or “liberals.”

A well-conceived and plausible falsehood, spoken or written at the proper moment gains popular credence, shapes thoughts and actions, and makes history.

Man is frail, is gullible, and is prone to err. He stands forever in need of fervent prayers and gentle guidance. The best of us stagger forward to ideals that seem always beyond reach.

The most fertile field for the communistic and “liberal” practice of the so-called “science” of cybernetics lies in the barren area left by our ignorance of the foundations of human liberty and dignity in America. Liberty has lost its landmarks. Its history is a blind spot.

Twenty-eight years ago an eastern university law-school senior, paying his way by tutoring American history, questioned certain conclusions of Dean J. H. Wigmore, late of Northwestern University, as to the history of a provision of the fifth paragraph of the Federal Bill of Rights. Soon this student had run the indexes in the law and general libraries of Columbia University. He not only found nothing on the history of the Fifth Amendment, but found nothing indexed on the history of the many other provisions of the Bill of Rights. Librarians were consulted. The casual and unconcerned reply was: “We have nothing.”

At the New York Public Library the answer was: “We have nothing.” At the Harvard and Yale University libraries, the answer was: “We have nothing.” Finally, at the Library of Congress, that supreme repository of the records of American civilization, the inquiring student stood speechless to hear the final verdict. It was: “We have nothing.”

A quick look at the indexes revealed mountains of books on the history of the Declaration of Independence, a document that accords no constitutional right and affords no constitutional immunity, a document no man could use then or now to shield his naked body from the lash of tyrants, a document that served a noble but temporary purpose in the American Revolution, but which never drew one breath as living law.

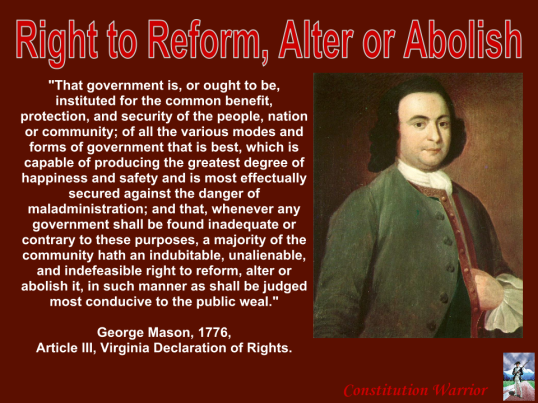

The indexes at Harvard University library revealed many thousands of volumes on fish. A recent news item disclosed that Harvard’s great Widener Library is the proud repository of 21,800 volumes on fish and fishing. But it does not yet contain one book on the history of the Federal Bill of Rights or any of those State bills of rights that preceded it and particularly the Virginia Bill of Rights, and upon which it was based. The most influential constitutional document ever penned by man was the Virginia Declaration of Rights of June 12, 1776. It was the grandfather of them all. Both it and its author await a Boswell.

The disillusioned and empty-handed student spent spare time for a full year, trying to find materials with which to set Dean Wigmore aright. Old unindexed records of American civilization were searched in boiler rooms and basements. Uncut leaves revealed that no other had traveled that way before.

At last he was able to piece together a semicoherent story of the historical evolution of the privilege against self-incrimination in America. A few years later the resulting paper was sent to Harvard Law Review, where it was rejected as uninteresting. Columbia Law Review rejected it for the same reason. Finally Virginia Law Review printed it as a space filler. Dean Wigmore picked it up in the third edition of his Work on Evidence, quoting that part of it that caused him to change and restate his views.(1)

Justices Black and Douglas are especially fond of it. The Supreme Court has since cited it many times. Dean Griswold, of Harvard Law School, used it in his article on the subject in the June 1954 issue of the American Bar Association Journal. The Attorney General, Herbert Brownell, Jr., used it in his address to the Law Club of Chicago on November 6, 1953, in which he told the lawyers of Chicago more than once to see Pittman, “The Colonial and Constitutional History of the Privilege Against Self-Incrimination in America” (21 Va. L. Rev. 793, et. seq.).(2)

Candor of mind displaced humility of heart, that I might tell that story for the first time. That student speaks to you now. Aside from and yet germane to the purpose we have in mind, we beg indulgence as we exercise the natural right of self-defense and quote one paragraph of that article. It has never been quoted in any reference we have seen in the mass of literature that cites Pittman to buttress Fifth Amendment Communists. Here it is:

This privilege against self-incrimination came up through our colonial history as a privilege against physical compulsion and against the moral compulsion that an oath to a revengeful God commands of a pious soul. It was insisted upon as a defensive weapon of society and society’s patriots against laws and proceedings that did not have the sanction of public opinion. In all the cases that have made the formative history of this privilege and have lent to it its color, all that the accused asked for was a fair trial before a fair and impartial jury of his peers, to whom he should not be forced by the state or sovereignty to confess his guilt of the fact charged. Once before a jury, the person accused needed not to concern himself with the inferences that the jury might draw from his silence, as the jurors themselves were only too eager to render verdicts of not guilty in the cases alluded to.

“Society’s patriots” in this Nation will need that “defensive weapon” and foxhole of liberty in the bleak winters ahead. Treasure and use it for the causes that our Anglo-Saxon forefathers intended it to be used. Stand mute before the bars of sociological injustice. Informed Anglo-Saxon jurors will do the rest. The privilege against self-incrimination was fashioned to parry the blows of just such a government as the Supreme Court seeks to impose upon us in 1954. In such a government, the last refuge of helpless man is “a jury of his peers,” with courage and virtue to render verdicts of not guilty. It was fashioned for cases where governments — not the governed — broke out of bounds — where rulers ruled by will instead of law.

In his great work on Civil Liberty and Self-Government (1880), at page 24, Francis Lieber said:

A people that loves liberty can do nothing better to promote the object of it than deeply to study it; and in order to be able to do this, it is necessary to analyze it, and to know the threads which compose the valued texture.

There is no surer way for a civilization to lose liberty than for it to lose, deface, ignore or destroy the charts which mark its springs and sources. We have done that. The repositories of our cultural records are virtually barren of any evidence as to the springs and sources of basic American liberties. The foundation stones of our freedom are as abandoned rubble.

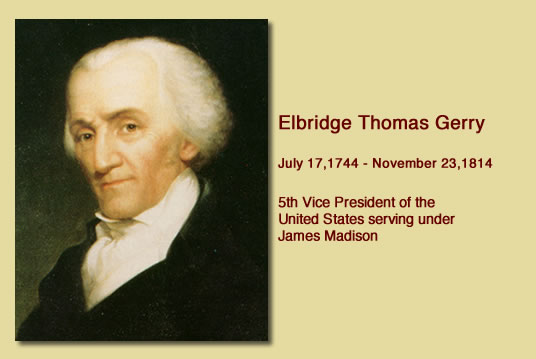

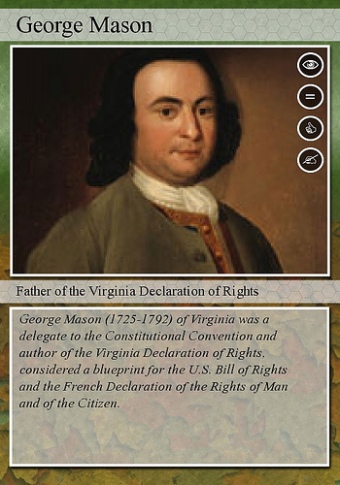

The shocking experience of the law school senior left in him an urge to place one book on the library shelves of America that would tell the history of each provision of the Federal Bill of Rights. For 27 years he accumulated materials. Hard earned and expended dollars soon became hundreds. Hundreds soon became thousands. It was early found that all the main roads of constitutional liberty in America bypassed big names to converge at last at a grand terminal with evolution’s pioneer George Mason, of Gunston Hall. It was found that big names had borrowed from that fearless, humble, godly and forgotten man. It was soon learned why Jefferson regarded him the wisest man of his generation, why Madison described him the greatest debater he had ever heard speak, and why Patrick Henry named him the greatest statesman he had ever known.

The search was renewed with Mason as a guide. It was rewarding. Microfilms, photostats, and other material accumulated. The project outgrew the researcher. The sympathetic chief justice of the supreme court of an Eastern State encouraged the researcher to apply at the portals of an eastern foundation for financial help to finish the job. The insulting reply discouraged any further opening for like humiliation. Hope matured into despair.

The Truman-sponsored National Historical Publications Commission was activated in 1951. Since Truman professed to be a historian, it was hoped that the Commission would list the father of our Bill of Rights as one whose papers were worthy of publication, but on the list of 121 published names of Americans whose writings were deemed worthy of publication the name of George Mason was not to be found.

Judge Felix Frankfurter was a member of the Commission and helped to make up that list. He preferred to list the papers of Andrew Carnegie, Tench Coxe, Ignatious Donnelly, Harvey Firestone, Samuel Gompers, Horace Greeley, Robert La Follette, Brigham Young, and Sidney Hillman as of more importance than those of the father of our most cherished freedoms. Frankfurter would guano American minds with trifles and mulch them with trash.

Ask cybernetic doctors of philosophy, “Who wrote the Federal Bill of Rights?” The answer most likely will be: “Thomas Jefferson.” One who has never been to school and can’t read and write may say: “I don’t know.” That would be about the only correct answer one would get.

A staff of 25 editors of Life magazine issued a publication in 1951 entitled “Life’s Picture History of Western Man.” On page 288 this book speaks of the Constitutional Convention of 1787, saying:

The delegates were fortunate in two respects: First, there were among them several great men — notably, Adams, Hamilton, and Madison — who not only believed in the Declaration [meaning the Declaration of Independence] but had taught themselves to know more about political philosophy than any men of their time.

In the next paragraph Life‘s editors described the limitations of powers reenforced by “Jefferson’s Bill of Rights.” In the same paragraph it was stated that Jefferson “aimed to give the Supreme Court a democratic bent by making it the guardian of his Bill of Rights.” They then gave John Locke credit for Jefferson’s “pursuit of happiness” phrase.

(1) John Adams did not attend the Constitutional Convention. He was in England. (2) Jefferson never wrote a single liberty preserving provision of any Constitution or Bill of Rights that has ever been adopted in America. (3) He never sat in a Constitutional Convention in his life and was in France while Mason’s struggle for a Bill of Rights was being waged. (4) He formulated his preamble to the Declaration of Independence, containing the equality and “the pursuit of happiness” phrases from George Mason’s Virginia Bill of Rights, adopted June 12, 1776, and John Locke had nothing to do with it. (5) The only connection Jefferson ever had with the Federal Bill of Rights was that he favored it from afar. (6) “Political philosophy” played no respectable part in the framing of our Constitution, and none in the Bill of Rights. Experience was the guide. John Dickinson expressed the idea well on August 13, 1787, on the floor of the Constitutional Convention, when he said:

Experience must be our only guide. Reason may mislead us.

There was only one philosopher in the Constitutional Convention of 1787. His name was Dr. Benjamin Franklin — one of the least influential men there. It has been noticed by several students of the Convention that he seemed to be the proponent of more rejected proposals than any other delegate.

If the editors of a great publication such as Life magazine pay such homage to philosophy and falsehood, how can we expect our children to know the historic truths that made and kept our ancestors free? A free press that knows not the author of its freedom will not long remain free.

Ask cybernetic doctors where Jefferson got the preamble to the Declaration of Independence. In unison, 98 percent of them will cry out, the philosopher, Dr. John Locke, and quote from a hundred books written by other doctors. Jefferson himself denied it many times, but most cybernetic doctors had rather make Jefferson out a liar than to admit that he worshipped at the feet of George Mason, who knew history and laughed at soothsayers. Some philosopher must be made to play the leading role in every great scene on the hill tops of history, even though he be a ghost.

The most intensely uneducated, ignorant and dangerous men in America are some of those who salve an inferiority complex by calling themselves doctors of philosophy or some pseudo-socio-science. The Un-American Activities Committee of Congress lists such doctors by the scores on their roll of treachery and dishonor.

The genealogy of the Declaration of Independence remains an untold story, though often told by doctors of cybernetics. Jefferson did not tell an untruth about it. When he said that it was not original with him but its source was the American mind, he told the truth. When he said he “copied from neither book nor pamphlet,” he excluded Locke, Otis and Paine and again told the truth. He didn’t exclude newspapers, manuscripts or circulars. That tip was the payoff but the cybernetic doctors all duck it. Those self-styled doctors prefer to lose it in John Locke’s philosophy, even if they must defy truth and defame both Jefferson and history.

Philosophy and sociology have always been the tamper tools that have sprung institutions of liberty out of alinement. Historical research and common sense born of experience, have always been the tools to spring them back into place. Doctors of pseudo-socio-science have always been the apes of tyranny.

A few days ago we glanced over the various constitutions of Alabama from her first until the last, printed in Thorpe’s Charters and Constitutions (1909). We found one provision traceable to Thomas Jefferson. It was in her carpetbag constitution of 1867. It was article 1, section 1, as follows:

That all men are created equal; that they are endowed by their creator with certain inalienable rights; that among these are life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.

That was forced upon the people of Alabama by carpetbag doctors of psuedo-socio-science, while Federal bayonets held the outraged white people at bay. As soon as those doctors were run out, Alabama called a constitutional convention, struck the first line, went back to George Mason, copying from the first paragraph of the Virginia Declaration of Rights of June, 1776:(3) “That all men are born equally free and independent.”

The carpetbag doctors put the same doctrine of equality into the constitutions of Arkansas, Florida, Louisiana, North Carolina, and South Carolina. Every one of these six States except North Carolina, heaved it as soon as the carpetbag doctors were driven out(4) North Carolina ran her carpetbaggers as far as her college campuses. There they swapped their title “Scalawag” for doctorates and there they have ever remained, screaming: “Academic freedom.”

George Mason’s original first line was, “That all men are born equally free and independent.” The Virginia convention changed it to read: “That all men are by nature equally free and independent.” Jefferson perverted it to read, “All men are created equal.”

We do not condemn Jefferson for converting the first three paragraphs of the Virginia Declaration of Rights into a preamble for the Declaration of Independence. But we do not commend him for playing the part of a gypsy, first defacing before claiming as his own. But men don’t stand on etiquette in the midst of revolution. Jefferson was writing, not to appeal to America but to appeal to France. America was in a death struggle. Washington commanded her troops long before July 4, 1776. The doctrine of equality then had a powerful appeal to the simple-minded peasant and philosophers of France. Jefferson was just giving them some cybernetics. He knew that France was a despotism tempered with epigrams. He knew the secret Napoleon later revealed at St. Helena when he said that the French mind wanted equality more than liberty and, it not being possible to give both, he gave them equality.

Jefferson was not a stranger to wisdom. He could have foreseen that which Lord Acton recorded many years later: “The deepest cause which made the French Revolution so disastrous to liberty was its theory of equality.”

Jefferson was an advocate, pleading America’s case at the bar of French public opinion. If “all is fair in love and war,” he was justified in appealing to the ignorant and shallow-minded philosophers of France with a false epigram, palatable to them, though abhorrent both to himself and to all America. He could not know that a Supreme Court would try to turn it into an “American creed” near two centuries later.

Jefferson indicted George III because: “He has excited domestic insurrections amongst us.” He clipped that from the South Carolina Constitution of March 1776, whose indictment read, “. . . excited domestic insurrections; proclaimed freedom to servants and slaves . . .” Again, a Jefferson defacement fooled France and her philosophers. It didn’t fool America then. Only fools are fooled now. Marxists and Communists never object or even refer to that clause of the Declaration of Independence. Servitude and slavery is a necessary concomitant of equality — look beyond the Iron Curtain.

Let it be said to the honor and glory of the American States, of the United States, and of the whole non-Communist world, that the George Mason concept of equality of freedom and independence under law took root in all of their constitutions. Faint traces of the Jeffersonian dialetical defacement may be found dangling like dodder in the declarations of rights of Idaho,(5) Indiana,(6) Kentucky,(7) North Carolina,(8) Massachusetts,(9) and Nevada.(10)

The original George Mason concept is both implicit and explicit in the constitutions of every one of those six States. It is to be found in all of our constitutions today and in more than one-half of the American state declarations of rights in the words of Mason. Paragraph after paragraph and clause after clause of the original phrases of George Mason are to be found in the fundamental laws of every American state, the United States Constitution and more than one-half the constitutions of the world. The equality clause of the Declaration of Independence never took root in America. The philosophy of equality beyond the range of legal rights dies in free soil. It thrives only in the sewers of Slavic slavery.

At a quick glance we identified 16 paragraphs of Alabama’s Declaration of Rights of 1901 as having been first framed by the pen of George Mason, before being recorded as preservatives of liberty in Alabama. They are as follows: Paragraphs 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 11, 15, 21, 25, 26, 27, 29, 35, 36, and 42. Jefferson is unknown to Alabama’s fundamental laws.

Of the 83 constitutions of sovereign nations of the world in 1950, 50 expressly preserved the old Anglo-Saxon concept of equality under law. The same concept is implicit and protected by safeguards in 78 of these constitutions. Only four contain the carpetbag concept of social equality. Those four are Guatemala,(11) the Mongol Peoples Republic,(12)the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic,(13) and the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics.(14)

Mongolia puts it this way: “Equal rights in all spheres of the state, economic, cultural, and sociopolitical.”

Russia puts it this way: “Equality of rights of citizens of the U. S. S. R. irrespective of their nationality or race; in all spheres of economic, government, cultural, political and other public activity.”

America expressed it in the 14th amendment with the phrase “equal protection of the laws.” The carpetbaggers that fell on Alabama in 1867, didn’t fall on the Nation in 1868. We can thank God for that.

Thirty-one of the constitutions of the nations of the world use exactly the same equality clause,(15) to wit: “Equal before the law.”

Each of the other 47 non-Communist nations use language that means the same thing. (See Peaslee, Constitutions of Nations.)

France rejected Jeffersonian advocacy to copy George Mason’s concept into her Declaration of Rights of 1789, in these words: “All men are born and remain free and equal in respect of rights.”

In the bath of blood we know as the French Revolution, Jefferson’s defacement replaced the Mason original in 1793, as follows: “All men are equal by nature.”

That substitution was symtomatic of the government of flesh that was to leave a tragic legacy in the history of France. After 153 years of sorrow, Jefferson’s advocacy was stricken and Mason’s concept went back into her fundamental law in 1946, exactly as it was in 1789.(16) Six years before, France had found the light in sackcloth and ashes. Her revolutionary motto: “Liberty, Equality, and Fraternity” was stricken from the tomb of her liberty. That cluster of inconsistencies no longer tarnishes the tricolor of France.

The doctrine of sociracial equality no longer stands forth in this world, except in four Communist countries and within the secret chamber of a strange Supreme Court of the United States.

On June 26, 1787, Alexander Hamilton, speaking on the floor of the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia said:

Inequality will exist as long as liberty exists. It unavoidably results from that very liberty itself.

Every mind assented.

It is inequality that gives enlargement to intellect, energy, virtue, love and wealth. Equality of intellect stabilizes mediocrity. Equality of wealth makes every man poor. Equality of energy renders all men sluggards. Equality of virtue suspends all men without the gates of heaven. Equality of love would stultify every manly passion, destroy every family altar and mongrelize the races of men. Equality of altitude would make the whole world a dead sea. Mountains rise out of plains. Plains rise out of the sea.

Equality of freedom cannot exist without inequality in the rewards and earned fruits of that freedom. It is inequality that makes “the pursuit of happiness” something other than a dry run or a futile chase.

On page 334 of his book (cited above) Francis Lieber said: “Equality absolutely carried out leads to communism.” Communism is but another name for equality in slavery. There can be no equality of freedom, without leaving to man his own free choice of the lawful “means of acquiring and possessing property, and pursuing and obtaining happiness,” as George Mason had it when Jefferson copied and defaced it from the first paragraph of the Virginia Declaration of Rights of 1776. The right to equality of freedom is a guaranty of the right to unequal shares of the earned fruits in freedom.

The recent decision of the Supreme Court on Segregation was one in which the Court was led into a vacuum by the cybernetics of sociological doctors, who found a judicial blind-spot and practiced a fraud upon the judges to victimize a helpless people. The most effective “expert” in cybernetics seemed to be Dr. Gunnar Myrdal, who wrote An American Dilemma (1944). His 1,483 pages of “psychological knowledge,” financed by Carnegie Foundation, controlled the Court. It was cited by the Court as the “modern authority” on which its decision was grounded. An American Dilemma is now Corpus Juris Tertius in American pseudo-socio jurisprudence.

Dr. Myrdal learned that the biggest blindspot in America is our abysmal ignorance as to the basic principles of American liberty. He found a vacuum or a vortex into which most anything could be thrown and it would pass for food. Thus he created an “American Creed,” that would have evoked universal laughter but for the fact that his creation was in a “blindspot.” Ignorance can’t laugh for fear of being laughed at. On page 4 of his atrocity he defined his “creed” as “the fundamental equality of all men.”

In the same breath he said its “tenets were written into the Declaration of Independence, the preamble of the Constitution, the Bill of Rights and into the constitutions of the several states. The ideals of the American creed have thus become the highest law of the land.”

He knew that what he said was an untruth, but he thought he was in a blind spot, and had that same feeling of security that an ambush gives to a midnight assassin.

Nevertheless for fear some unbeliever might cite the Constitution on him he put his shoes on backwards to make tracks both ways. On pages 12-13 he said:

Conservatism, in fundamental principles, to a great extent, has been perverted into a nearly fetishistic cult of the Constitution. This is unfortunate since the 150-year-old Constitution is in many respects impractical and ill-suited for modern conditions . . . The worship of the Constitution also is a most flagrant violation of the American Creed . . . which is strongly opposed to stiff formulas.

On page 18, lawyers and judges became anathema to the American people and the “American Creed,” because, as he says, the “judicial order . . . is in many respects contrary to all their inclinations.”

As his cybernetic pages of Slavic philosophy are turned, the “American Creed” becomes the amalgamator of races. On page 614, “. . . the cumbersome racial etiquette is ‘un-American.'”

He praised Thomas Jefferson to heaven on page 8 for the equality content of the specious “creed,” which he claims to have found in the Declaration of Independence. But he again reversed his shoes on page 90 and damned him to another place for proposing emancipation and simultaneous segregation of Negroes to Africa, in his Notes on Virginia.

While reversing his shoes in rapid succession, his socks slipped off. What an odor. On page 9 he exposes a half-concealed truth in the midst of half-truths. Here it is:

Against this [liberty] the equalitarianism in the Creed has been persistently revolting. The struggle is far from ended. The reason why American liberty was not more dangerous to equality was, of course, the open frontier and free land. When opportunity became bounded in the last generation, the inherent conflict between equality and liberty flared up. Equality is slowly winning. The New Deal during the ‘thirties was a landslide.

For once Dr. Myrdal told the God’s truth. Liberty and equality cannot coexist. The Supreme Court of the United States affirmed that truth and used equality to destroy liberty. Dr. Myrdal is the modern authority on that truth. Was that the purpose of Carnegie Foundation in financing Myrdal’s atrocity? John W. Davis is one of the Carnegie trustees. He is a lawyer. He defends Carnegie Foundation with the same mind he used to defend the Constitution and the Anglo-Saxon race. Before a committee of Congress, he defended Carnegie’s employment of Alger Hiss, and his retention after his treason was known, by pleading stupidity. The blindspot in his mind must have been a cavern — a heaven for cybernetics.

The Supreme Court specifically held that the records in the so-called segregation cases affirmatively disclosed that the “separate but equal” formula laid down in Plessy v. Ferguson (163 U.S. 537), had been fully and completely complied with, and that equality of white and black schools in respect to all tangible factors had been demonstrated beyond doubt. The Court thus found itself faced with three alternatives: (1) It could adjudge according to law and facts and find in favor of segregation; (2) it could usurp the powers of a Constitutional Convention and give to itself power to legislate against segregation; or (3) it could copy Dr. Myrdal and Ananias, usurp the power of God, and make new facts. It chose both alternatives (2) and (3) and made a new constitution and new laws for the cases, and new facts for the records. It did not hold Plessy v. Ferguson to be bad law. It held it to be bad sociology, according to Dr. Myrdal, the modern authority.

Unabashed, the Court went back to the records in the graduate school cases of Sweatt v. Painter (339 U.S. 629), and McLaurin v. Oklahoma Regents (339 U.S. 637), and extracted from them what the Court described as “intangibles” and transplanted them into the Kansas, South Carolina, Virginia, and Delaware case records, then before the Court.

Next the court found an intangible lurking in the Kansas record that the trial judge had discovered by a new process of psychoanalysis. It was that segregation generates a sense of inferiority and that such “a sense of inferiority affects the motivation of a child to learn.”

The court didn’t stop to consider whether the effect was good or bad. Most psychologists hold that an inferiority complex increases the motivation of a child to learn, but the Supreme Court could not afford to subject Dr. Myrdal’s cybernetics to the light of reason. It transplanted that unevaluated, and hyprocritical intangible into the records of the South Carolina, Virginia, and Delaware cases in order to fill vacuum with void. By that time the Court had lost all sense of reason, direction, and proportion. It then doubled back to fill void with vacuum. Here is the new intangible that made its first appearance in Anglo-Saxon jurisprudence and its last in a government of law:

Whatever may have been the psychological knowledge at the time of Plessy against Ferguson, this finding is amply supported by modern authority.[11] Any language in Plessy against Ferguson contrary to this finding is rejected.

The modern authority as set forth in footnote 11 is quoted below.(17) It is sociology, not psychology.

Modern authority is not law. The Court said it wasn’t. It is not within the remote boundaries of the science of law. It first made its appearance as gossip, in whispers and undertones in the secret chambers of the judges. It is not evidence, because, as said by Mr. Justice Brandeis in U.S. et al v. Abilene & Sou. Ry. Co. (265 U.S. 274, 288):

Nothing can be treated as evidence which was not introduced as such.

Modern authority was never introduced in evidence in any of the cases. It couldn’t have been admitted if tendered, because it was hearsay and gossip. No court this side of Moscow admits such evidence.

In Ohio Bell Telephone Co. v. Public Utilities Commission of Ohio (301 U.S. 292), the Supreme Court held, by a full bench, that to treat anything as evidence which was not introduced as evidence, denies to the complaining party “due process of law,” as guaranteed by the 14th Amendment. By the same reasoning, like judicial misconduct on the part of a Federal court is a denial of Fifth Amendment “due process of law.” Thus Virginia, South Carolina, Delaware, and Kansas parties were denied “due process of law” by the very Court that had held such to be unconstitutional. “Sauce for the goose is sauce for the gander,” even though the gander struts.

In that Ohio case, the commission transplanted factual findings from an Illinois Federal case into the Ohio record. It also transplanted therein “information secretly collected” by the judicial body. Exactly what the Supreme Court did in the segregation cases. When asked for an opportunity to examine, to explain, and to rebut them by the injured party in Ohio, the response was a curt refusal. In the so-called segregation cases no opportunity was given to ask. The whole thing was kept secret until the judgment was announced. Justice Cardoza spoke for the Supreme Court, in the Ohio case, with indignation:

The fundamentals of a trial were denied to the appellant. . . . This is not the fair hearing essential to due process. It is condemnation without trial . . . This will never do if hearing and appeals are to be more than empty forms . . . There can be no compromise on the footing of convenience or expediency . . . nothing . . . gave warning . . . of the purpose of the commission to wander afield and fix . . . [the facts] . . . without reference to any evidence, upon proofs drawn from the clouds. As there was no warning . . . there was no consent to it. We do not presume acquiescence in the loss of fundamental rights.

Cardoza is no more, but Black is. In National Council of American-Soviet Friendship, Inc., et al. v. McGrath (341 U.S. 123), a group of organizations listed and publicized as communistic by the Attorney General were complaining that the Attorney General had acted on secret information without notice and a fair hearing. Justice Black was enraged. His sociological blood ran hot. We quote him as he tempered the wind to the shorn lamb skins that concealed the communistic wolves:

The heart of the matter is that democracy implies respect for the elementary rights of men, however suspect or unworthy; a democratic government must therefore practice fairness; and fairness can rarely be obtained by secret, one-sided determination of facts decisive of rights.

. . . The plea that evidence of guilt must be secret is abhorrent to free men, because it provides a cloak for the malevolent, the misinformed, the meddlesome, and the corrupt to play the role of informer undetected and uncorrected. Appearances in the dark are apt to look different in the light of day. . . .The validity and moral authority of a conclusion largely depend on the mode by which it was reached. Secrecy is not congenial to truth-seeking and self righteousness gives too slender an assurance of rightness. No better instrument has been devised for arriving at truth than to give a person in jeopardy of serious loss notice of the case against him and opportunity to meet it. Nor has a better way been found for generating the feeling, so important to a popular government, that justice has been done.

An “opportunity to meet” Myrdal with a pointed cross-examination would have withered him in a few minutes. What a dissertation he would have given on George Mason’s constitutional privilege against self-incrimination. He might even had cited Pittman on the history of it.

In Stromberg v. People of California (283 U.S. 359), Stromberg had been convicted in California for violating a statute forbidding the display of a red flag “as a sign, symbol, emblem of opposition to organized Government or as an invitation or stimulus to anarchistic action or as an aid to propaganda . . . of a seditious character.”

The Supreme Court reversed the case, holding that it was a violation of the 14th Amendment thus to trample upon the banner of Communism and strike its flag of treason.

However, in Beauharnais v. People of Illinois (343 U.S. 250), the shoe was on another foot and turned backward. The Supreme Court stated the facts as follows:

The information, cast generally in the terms of the statute, charged that Beauharnais did unlawfully . . . exhibit in public places lithographs, which publications portray depravity, criminality, unchastity, or lack of virtue of citizens of Negro race and color which exposes [sic] citizens of Illinois of the Negro race and color to contempt, derision, or obloquy . . . The lithograph complained of was a leaflet setting forth a petition calling on the mayor and city council of Chicago ‘to halt the further encroachment, harassment, and invasion of white people, their property, neighborhoods, and persons, by the Negro . . .’ Below was a call for one million self-respecting white people in Chicago to unite . . ., with the statement added that if persuasion and the need to prevent the white race from becoming mongrelized by the Negro will not unite us, then the aggressions . . . rapes, robberies, knives, guns, and marihuana of the Negro, surely will. This, with more language, similar if not so violent, concluded with an attached application for membership in the White Circle League of America, Inc.

In his opinion upholding the conviction of Beauharnais, Justice Frankfurter expatiated on the terrible racial troubles in Chicago and vicinity, describing the race riots in that non-segregated area, such as are unknown to the segregated South because of segregation. He said:

Only those lacking responsible humility will have a confident solution for problems as intractable as the frictions attributable to differences of race, color, or religion. . . . Certainly the due-process clause does not require the legislature to be in the vanguard of science — especially sciences as young as human ecology and cultural anthropology.

. . . It is not within our competence to confirm or deny claims of social scientists as to the dependence of the individual on the position of his racial or religious group in the community.

So the Red banner streamed in California, while Beauharnais served his sentence in Illinois, because the Court didn’t have the competence to evaluate racial issues in a science as young as human sociology.

The Supreme Court just had too much humility to say that Illinois had run afoul of the constitutional rights and liberties of Beauharnais. Human sociology and cultural anthropology were just too young in 1952. The Court thus humbly disavowed its competence to confirm or deny claims of social scientists on racial issues.

Never before, in all recorded history, have human sociology and judicial competence blossomed before they budded. Never before have such flowers been plucked from the same vine.

When color alinements changed from white to black, and from red, white, and blue to red, human sociology and judicial competence descended upon the Court like an avalanche. Judicial humility lost its virtue to a strange and alien suitor in the secret chambers of the Supreme Court on May 17, 1954. Liberty under law was then and there prostituted by the depraved philosophy of equality under sociology.

A civilization that lets carpetbag doctors paint the alien equality philosophy of Karl Marx on the minds of its children for one whole generation cannot expect them to retain their liberties. Presidents who systematically exclude lawyers from the supreme judicial bench can have no wish to retain the liberties of the people.

Under our common law and under our Constitution, no man or body of men may make law for freemen except the elected representatives of the people. Every freeman in a republic has the despotic right to veto all laws made by any man or group of men except his own delegates. For 500 years Anglo-Saxon freemen have exercised that veto power. Only a blind spot in our knowledge of history could cause any man to doubt the right of any freeman to disobey the unconstitutional edicts of a judge or king. Only fools and pseudo-socio-doctors contend that the Supreme Court can make law, but of such is the kingdom of tyranny. Constitutional liberty is the child of Anglo-Saxon history, christened by the blood of our fathers. How could we so soon forget that the leading principle of the American Revolution was that only delegates chosen by the people may make constitutions and laws for the people? Every forgotten grave from Lexington to Yorktown is a memorial to that principle.

We have no answer to the dilemma. It may be too late. Liberty is lean. In his Virginia bill of rights, George Mason said: “That no free government, or the blessings of liberty can be preserved to any people but by a firm adherence to justice, moderation, temperance, frugality, and virtue, and frequent recurrence to fundamental principles.” None but a fool would dispute his word. None but a fool, or a cybernetic doctor, will tell you that liberty and equality may grow in the same soil.

Equality reaches into the pockets of the frugal to put fat on lazy bones. Fat fools don’t fight, except at the trough. From the trough of equality there may be no road back. The next gate may lead to slaughter pens or to the mines of Siberia. We may have lost the will to be free.

In closing we mention one answer taken from the history of the sanguinary struggles of the Anglo-Saxon race to retain liberty under law. The one word that best describes it is segregation. The very gates of heaven were built for the sole purpose of segregating the good from the bad and the true from the false. The God who segregates beyond the earthly grave by the principle of inequality, segregated the races of men in the beginning by the principle of color, placing the yellow man in Asia, the black man in Africa, the white man in Europe, and the red man in America. We must not be afraid to practice his principles.

At the peak of the tyranny of the sociological Stuart kings in England, our forefathers segregated the royal court and every friend of the court. As Charles I rode from Whitehall to Guildhall and thence into the city of London, with his armed guards, seeking to effect the arrest of five members of Parliament for opposing his tyrannies in 1641, multitudes lined the streets. Everywhere Charles I turned, his eyes were met by cold stares. The only greeting he heard was “Privileges of Parliament.” “Privileges of Parliament.” A man by the name of Walker boldly stepped forth and planted a pamphlet in the royal carriage at the King’s feet, entitled “To Your Tents, O Israel.” Thereafter wherever the King and his friends were seen they were greeted: “To Your Tents, O Israel.” As Charles I went to the block to lose his head, the crowd cried out to him: “To your tents, O Israel.”

Forty-five years later that watchword of freedom was still ringing in the ears of old Judge Jeffries of the Bloody Assizes. At the trial of Richard Baxter, in 1685, Jeffries was in a rage. From the bench and before the royally packed jury, he screamed at Baxter: “Time was when no man was so ready to bind your king in chains and your nobles in fetters of iron, crying, ‘To your tents, O Israel.'” As Jeffries cheated the gallows to die in London Tower, rather than on Tower Hill, “To your tents, O Israel” was the last sound recorded in his depraved mind.

In 1773, as the chains of slavery were being forged for our forefathers in the American Colonies, the Sons of Liberty revived that old Anglo-Saxon watchword. Socio-judicial prostitutes were chilled to the marrow of their bones as they constantly heard that cry, and saw it written on roadsides. When they tried to hold courts on Massachusetts circuits, jurors called to the bar stood mute and took no oaths.

The irate socio-judicial tools of tyranny were finally led from the bench at Worcester by an orderly crowd of 5,000 patriots and gently caused to walk between parallel single files, each of 2,500 patriots and were gently forced to disavow, 30 times, compliance with the tyrannical laws of England they were sent there to enforce — 30 times. A symbol of the 30 times Parliament had been forced to reaffirm Magna Carta on account of depraved kings’ judges who had destroyed governments by laws in England and driven our forefathers to American shores. As those judges were herded to a haven to his majesty’s ships, the last words that rang in their ears was, “To your tents, O Israel.” Samuel Adams was the brain behind it in New England. Segregation was the secret. Every traitor to his land and race was segregated.

In Virginia the committee system was instituted. George Mason was the brains. George Washington was Mason’s most effective segregator. The Washington papers in the Library of Congress still contain the papers George Mason wrote for Washington to circulate for signatures. In fact, Mason wrote every state paper Washington ever carried in his pockets before he assumed command of the continental army before Boston. Washington went to Williamsburg with Mason’s Fairfax County Resolutions in his pocket in the spring of 1774. There they became the Virginia Resolves in the summer, and at Philadelphia they became the Continental Resolves in the fall. Listen to the old Anglo-Saxon doctrine of segregation in paragraph 20, “that the respective committees of the counties, in each colony . . . publish by advertisements in their several counties, a list of names of those (if any such there be) who will not accede thereto; that such traitors to their country may be publicly known and detested,”

Every traitor was segregated in order that America might regain its freedom. Every traitor must be segregated in 1954 that we may retain that freedom they won for us. The Anglo-Saxon race must again emulate the Founding Fathers and organize to fight fire with brimstone. “Sons of Liberty” is an honored name for such an organization. “To your tents, O Israel”(18) is an honored watchword. Above all remember this: Samuel Adams and George Mason had brains and character. There is no substitute for those qualities at the top.

NOTES

1. Wigmore on Evidence, 3d edition, vol. 8, p. 303 et seq.

2. His speech reported in Tulane Law Review, December 1953, vol. 28, p. 1.

3. Art. 1, sec. 1, Alabama constitution, 1875.

4. In Arkansas constitution art. 11, sec. 1, 1864; out, art. 11, sec. 2, constitution 1874; in Florida, art. 1, sec. 1, 1868; out, art. 1, sec. 1, 1885; in Louisiana title 1, art. 1, 1868; out, 1879. maryland, 1864; out, 1867. In, South Carolina, art. 1, sec. 1, 1868; out, 1895.

5. Idaho (art. 1, sec. 1, constitution, 1889).

6. Indiana (art. 1, sec. 1, constitution, 1851).

7. Kentucky (sec. 1, constitution, 1890).

8. North Carolina (art. 1, sec. 1, 1868).

9. Massachusetts (pt. 1, art. 1, 1780).

10. Nevada (art. 1, sec. 1, 1864). (See Thorpe’s Charters and Constitutions alphabetically and chronologically arranged.)

11. Art. 23.

12. Art. 79.

13. Art. 103.

14. Art. 123. (See Constitutions of Nations, alphabetically arranged, by Peaslee (1950).)

15. Albania, art. 12; Argentina, art. 28; Belgium, art. 6; Brazil, art. 141, Bulgaria, art. 71; Burma, art. 13; China, art. 7; Costa Rica, art. 25; Cuba, art. 20; Czechoslovakia, sec. 1; Egypt, art. 3; El Salvador, art. 23; Finland, art. 15; Haiti, art. 11; Ireland, art. 40 (1); Italy, art. 3; Japan, art. 14; Korea, art. 8; Lebanon, art. 7; Liechtenstein, art. 31; Luxembourg, art. 11; Monaco, art. 5; Nicaragua, art. 109; Panama, art. 21; Paraguay, art. 33; Rumania, art. 16; Switzerland, art. 4; Thailand, Sec. 27; Turkey, art. 69; Uruguay, art. 8; Yugoslavia, art. 21.

16. Peaslee, Constitutions of Nations, Vol. II, p. 21.

17. K. B. Clark, “Effect of Prejudice and Discrimination on Personality Development” (Midcentury White House Conference on Children and Youth, 1950); Witmer and Kotinsky, Personality in the Making (1952), ch. VI; Deutscher and Chein, “The Psychological Effects of Enforced Segregation: A Survey of Social Science Opinion,” 26 J. Psychol. 259 (1948); Chein, “What are the Psychological Effects of Segregation Under Conditions of Equal Facilities,” 3 Int. J. Opinion and Attitude Res. 229 (1949); Brameld, “Educational Costs, in Discrimination and National Welfare,” (McIver, ed., 1949), 44-48; Frazer, The Negro in the United States (1949), 674-681. And see generally Myrdal, An American Dilemma (1949).

18. This was the watchword of revolt of the 10 tribes of Israel, when they separated from Rehoboam.

This speech was published in several periodicals including The Alabama Lawyer Vol. 15, p. 342,

and in Vital Speeches of the Day, Vol. 20, p. 754 (No. 24), October 1, 1954.

http://rcarterpittman.org/essays/misc/Which_Shall_It_Be.html

Posted in

Consitution and tagged

Adams,

American,

Americanism,

anti federalist papers,

Bill of Rights,

Constitution,

Declaration of Independence,

Founding Fathers,

Freedom,

Freeman,

Hamilton,

history,

Jefferson,

Liberty,

Madison,

MAson,

Originalist,

Philadelphia,

politics,

Supreme Court,

United States,

Virginia,

Washington |

![]() Papers 3: 1079

Papers 3: 1079